There was no planned musical evening, but I can’t help but share this. Enjoy!

Bow v.2

My cry did not go unanswered! Now we have a wonderful girl working with us who creates equally wonderful things. Even without being here, she was able to depict this from my vague verbal description and crooked drawings onion, and did it just fine.

Here she herself, and here it is public, which has a lot of good things in it.

Tuesday - the day is not much better

We continue the story with the days of the week. We started - that means we need to finish.

- six-day week: among the Glinnar elves and the Sadorei elves. Apparently, it arose among them at the stage when they were one and only people. Glinnar days of the week are called as follows:

- saitya (saithia) "new"

- linya (línia) "lunar"

- telya (thélia) "star"

- gerya (geria) "light"

- fedya (fedhia) "fiery" (or "solar")

- yerya (ieria) "old"

The Sador ones are exactly the same in meaning and form: šúihttea, linnea, tallea, norrea, páđđea, iárrea.

— a five-day week among the Dverg-Kharassukhumi people. These were distinguished by a somewhat strange imagination and named the days haṭaxel "one night" moñquxel “two-night”... They probably liked it better that way. Hard to tell.

- incomprehensible game - among the Eryakhshar dzherts. After three eight-day weeks there was one six-day week, then again three eight-day weeks and one six-day week... This is mainly due to their calendar, but more on that another time.

The days of the eight-day week were simply called ordinal numbers: rāz̧ef "first", teref “second”, ... Six-day days - borrowed from the Glinnar people and look like saţya, līnya, ţelya, geria, fēḑya, ērya.

Somehow this post turned out to be quite small compared to that one. Well, nothing!

Old clothes

And yet another thing. The thing is not too frequent, but not too rare either; known to many, but not to everyone. In general, we found several sets of clothes of the Glinnar elves. But the clothes they wore… fifteen thousand years ago?

Dating is a little tricky, but such clothes are literally the first relatively civilized Alf attire known to history. It appeared even when the ancestors of modern Glinnarians lived in tropical and subtropical latitudes.

It consists of:

- a long piece of gray linen, which is wrapped two or three times around the hips. From the middle of the thigh to the very bottom on the left and right sides it has a cut to the very bottom;

- in the upper part, at the waist, the canvas has holes through which a leather cord is threaded - it holds the whole structure and prevents it from falling off;

- a relatively wide embroidered belt is worn over this;

- on the shoulders - a cape with ties; also either from linen, or leather or woolen;

- on the feet - sandals;

- OPTIONAL: on the hands - two-layer leather bracers on a fabric lining.

The male from the female, if anything, does not differ at all, that's why I painted it only on the male figure. I did not add bracers, because they were not used so often (although they are in almost all the sets we found). I think a little later I will ask our artist to draw everything in colors: the embroidery is very beautiful, it’s a sin not to show it.

Notable characters

The further I go, the later I write posts, because during the day the heat is unbelievable and I just want to melt. But let's get started anyway.

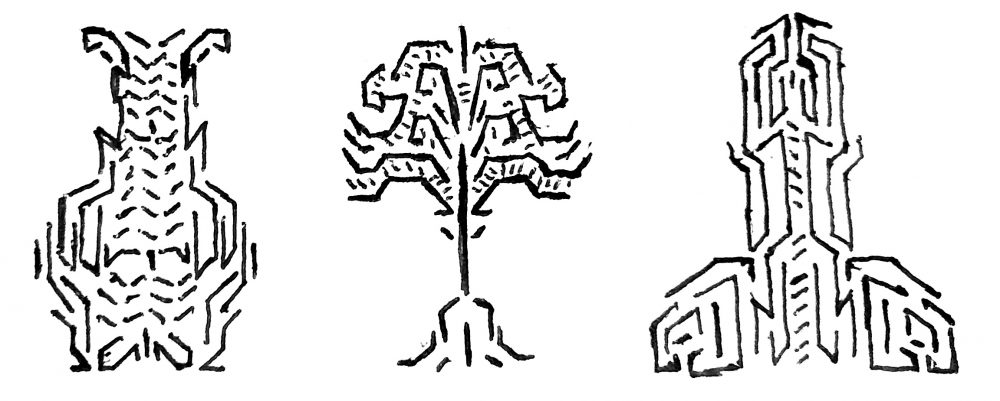

What a find! As is known, the Harassukhum dvergs - both men and women - applied certain tattoos to their heads, which had a sacred meaning. The women then grew their hair back, but the men often did not - they shaved their heads. This is just a short historical excursion, just in case.

We found a drawing of the three most popular images, starting from... the third century, I guess? It's a jug of water (oddly resembling a beetle), a tree and... I'll console the most shy by saying that it's a rocket. I'll tell the rest of you the truth - it's a phallus. Yes, they wore it on their heads and showed it to people. A symbol of fertility and all that. Cultural traditions!

The drawing was done very carelessly and in a hurry - I tried to redraw it in approximately the same way. It is difficult to say why. Perhaps the person who drew it did it secretly and did not want to get caught.

Monday is a hard day

Let's talk a little about the days of the week? Because... why not.

The seven-day week appeared in Orov relatively long ago, but not by itself. It was borrowed from the Daids, passed on to the Hellenes and the Romans, and then spread in all directions and has been doing quite well ever since. But the names of these very days differ somewhat from nation to nation.

- Derived from numerals. These are:

- we are with you, comrades (we will tactfully skip Saturday and Sunday);

— piles: pirmadienis, anthradiones, …;

- the Greeks. They, however, have a "second day" (Δευτέρα) - this is our Monday, Sunday is called Correspondence (Lord's Day), Friday - Paraskeui - "preparation (for Saturday)", but these are also trifles;

— and a few more of our close neighbors.

That's all, by and large.

- From the names of deities

— novels and all their descendants. For example, the Hessian lundi comes from Romance Moonlight "Moon Day" mardi — from Martis died "Mars Day" and so on.

- betas - they simply stole everything from the novels and sporadically replaced some days with their own new formations;

— Germans. They did the smartest thing — they took Roman names and replaced Roman gods with their own. Very convenient. If they had a seven-day week before (which is doubtful), then they probably also simply numbered everything with numerals, like the Svaites. - What a wild thing

There are several examples that can be given here, but I will only talk about the Ausks.

- Monday - astelehena "first of the week". Good;

- Tuesday - asthetica "in the middle of the week". That's weird;

— Wednesday — asteazkena "end of the week". Questions begin to arise;

- Thursday - osteguna "Orci (local heavenly deity) day";

- Friday - ostirala - something also connected with this Orci;

- Saturday - larunbata "fourth". At this point I just cast off;

- Sunday - igandea. And here there is no clear etymology at all.

Now I understand that I wanted to tell not only about the seven-day week, but also about other versions, but... there is already too much text! So until next time =D

Vişē fuğaxn

Today I did a little work on “Words about Walking,” and just in case, I re-read the existing pieces of text to refresh everything in my memory. And I came across a thing that I screwed up in an absolutely terrible way.

In the very first text, in a short note from the author, we see the following words: “all the evil brothers", "The two of us fraternized through an oath." And they translated them as simply “we fraternized,” omitting the “oath” - in any fraternization ritual, certain oaths are taken, right?

Overall, this is a very, very big mistake. I sprinkle ashes on the top of my head, which is already starting to grow, and explain what exactly we missed.

Five minutes of searching on the Internet was enough for me, Zear and Berenice to find a thing called vişē fuğaxn, which means “oath of allegiance” in Geartoi. It would take a long time to talk about its origins and other things, so the most important fact is immediately clear: the Gearts who brought it to each other became more than just brothers. They, in essence, thus expressed a desire to have a common family, common offspring, common... literally everything! Just in case, let me remind you that the Eryakhshar families were entirely polygamous: both on the male side and on the female side.

That is, such an oath was sworn to each other by people who were very close to each other. And in the text, since the author (Motley) so emphasizes that it was “the curse” that he and Viryaz fraternized, this is probably what is meant. Because otherwise I can’t imagine why specifically pointing this out.

The question arises. How did it happen that a geart and a man swore an oath of this kind to each other? What the hell is this anyway?

Bracers!

I deliberately waited until today: I hoped that the bot that reposted on Telegram would come to life. Alas, the miracle did not happen; They have some kind of showdown with the provider, so all we have to do is wait.

In the meantime, post. About those same bracers. And they look like this:

- a leather base, under which there probably should have been a fabric lining - it disappeared somewhere, apparently;

- Metal scales are overlapped on top of the skin. And not simple ones, but made of some kind of titanium alloy, that’s it!

- secured as follows: each scale on the inside has something like a rivet, with which it is attached to the skin. In addition to it, each scale also has a small hole - a thread is threaded through them and fastens the scales themselves together so that they do not move apart or unfold.

Additionally, it is worth considering that the bracers themselves are simply incredibly huge. They were clearly made for a person, but... for some kind of giant man. I have some guesses about who it could be, but for now it’s better to keep quiet so as not to get into trouble.

From the closest thing we could find online to our find, keep the photo in the header. There are two main differences: the scales on our bracers are slightly smaller and are not fastened with any metal rings.

Writing instruments

The post about bracers will be! My guess was right. Until then, here are some random historical facts.

Writing appeared in the Orova territories a long time ago. The first, of course, were the Glinnar elves, but I don't want to talk about that. Any writing presupposes the presence of two objects: something to write on and something to write with. We'll talk about writing utensils now!

- Glinnar elves. They used lodrast (lodrast) — a unique kind of paper made from reeds and (!) abandoned wasp nests. They wrote with brushes made of goat hair (cheaper) or squirrel hair (more expensive), similar to those that are still used in Mynyak and Yashut calligraphy. Oh, and they used ink, yes, black or colored.

- Draghars. In their reptilian form, they wrote with claws or metal styluses on molten stone. Effectively, but slowly.

- Eryakhshar dzhearts. They used sharpened and split at the end sticks made of reed. The highest class is if all the sharp edges of such a stick are rounded so that it does not scratch... lodrast! Which they first bought from the elves, and then learned to produce themselves.

- Harassukhum dvergs. These had a long history: starting with clay and stone tablets and ending with... yes, you guessed right. The same lodrast, which they now imported from Eryakhshar - simply because it was closer and easier. To write on it, they first used thin sticks of ink, which were moistened in water, and then they learned to produce graphite of good quality, and something like pencils came into use.

- I think you already know about the Rechansk and regional birch bark, all kinds of parchments and other things =D

News and drawings

Some new news!

I have delegated a good half of my responsibilities to Berenice, which is why she is now suffering just as I have been suffering for the last two weeks. However, now we have a kind of stagnation at the excavation site: already so many materials, monuments and various other finds have accumulated that you just have time to study, research, describe, translate them... well, you understand, yes. If there is something really interesting, we will tell you. And it is very likely that it will be: I heard something out of the corner of my ear about ring-plate bracers, which look quite unusual. Let's see, in short.

My hobby, related to writing art, is beginning to grow and take on terrible proportions. For example, today an idea popped into my crazy head that I just can’t get rid of. There is such an Eryakhshar poem, “Song of Strange Love,” written in the 9th-8th century BC. Tells about the love of a jeart for a person; What is characteristic is that neither the author is really known, nor even his gender.

Here's the idea. Since the poem narrates everything almost entirely in the past tense, classical translations into Retzin use the masculine gender: “did,” “remembered,” and so on. But why not, I thought, try to avoid explicitly indicating the gender of the hero of this poem? Paraphrase, change the tense, do something else so that the translation has the same unspokenness as in the original.

Zear said that I was completely gone, but if anything happened, he was ready to help. And this is very beneficial to me: he is the bearer of the modern Geartoi, and he has not changed that much over the past two-plus millennia.

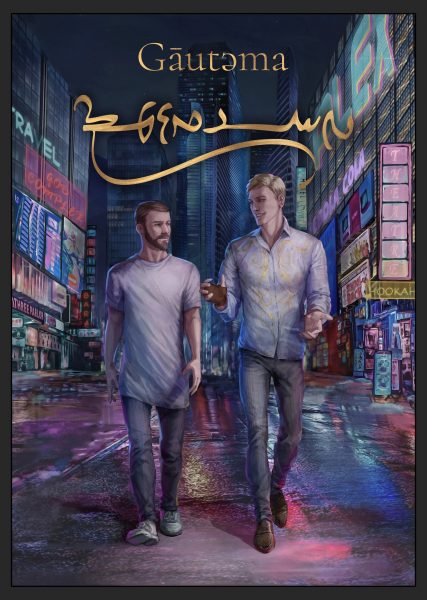

And one last thing. Amazing artist Mara Voev I drew the cover for my cyberpunk writing. I am attaching the original drawing with the title already attached. Thanks her!

Good night to you.