A little light historical excursion.

What type of stringed instruments do you think had the greatest variety and distribution? Alvov? Dvergov?

But no! Geartskie. Why is that? The answer is very simple and obvious: they have claws, which were very convenient for plucking strings. This, however, imposed some restrictions: for example, it is difficult to play a guitar with claws - as, indeed, on a violin, a cello, and in general on any instrument whose strings need to be pressed against the neck. There were two ways out of this situation:

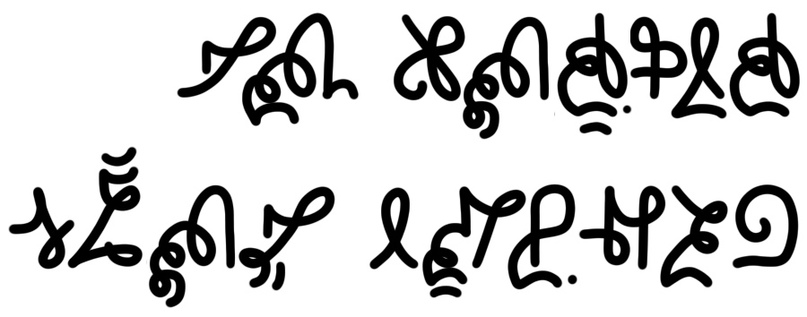

- We used instruments where the strings do not need to be pressed against the fingerboard. As far as we can judge now, there were simply incredibly many varieties of them; Their names have not been preserved, for the most part, but they ranged from gusli and zither to koto and guzheng. They differed mainly in the arrangement of the strings in the horizontal plane, the method of tuning and the height of the strings: if they are located high enough, then with the fingers of one hand they can be divided into parts, while producing higher sounds, as on a modern guqin.

- We used a notched neck. The funny thing is that it was rediscovered relatively recently (look, for example, scalloped fretboard). The Gearts stopped using it because, starting in the tenth century, they began to undergo operations to retractabilize the claws, and the need for such vultures naturally disappeared. And they reintroduced it into music for a completely different reason: the strings on such a neck can be deliberately pressed lower than necessary in order to extract microtones and various similar things.

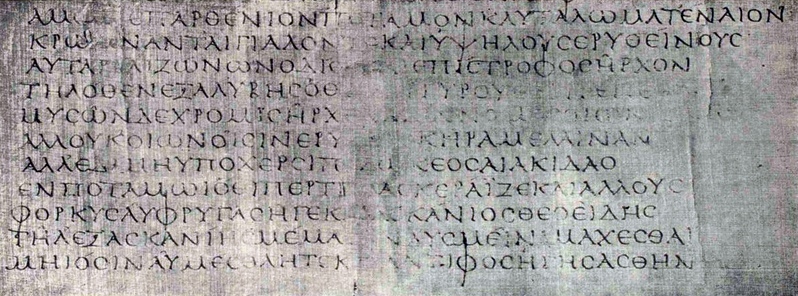

And another one of the Aznat Dzheart tribes was the first in the world to invent bows. Their men specially grew their manes almost to their waists and took care of them in some special way, all for the sake of art! There is still debate about what is better to use for bows: horsehair or Geart mane.